An introduction to Personal Construct Psychology

By John M. Fisher

Personal Construct Psychology (PCP) is a psychology that places the individual at its central focal point. It is based on understanding the individual from within their own world view – that is by understanding how they see the world not how we interpret their picture of the world. We all interact with the world from a unique perspective – our own, this interaction is built up of all our past and potential future experiences and dictates how we approach situations.

PCT is a very personal model focused solely on the individual and their interactions with, and in, their worlds. It’s an approach that is highly self-reflexive and looks at how the individual understands, interprets and interacts within their own world. This is in direct contrast to much of psychotherapy, where an outside “expert” gives their interpretation of someone else’s world and both then acts as if that is true.

It is also a tremendously powerful, and liberating, model in that it gives power, and agency, directly back to the individual – they have the power to choose from any of the options they believe are available to them. however it’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness!, because it is so empowering and individually focused it can cause some philosophical problems when trying to extrapolate to groups and societies.

Also, because it is individualistic and based on personal perception, it is only by really understanding how other people see their worlds that we can effectively interact with them in a meaningful and effective way.

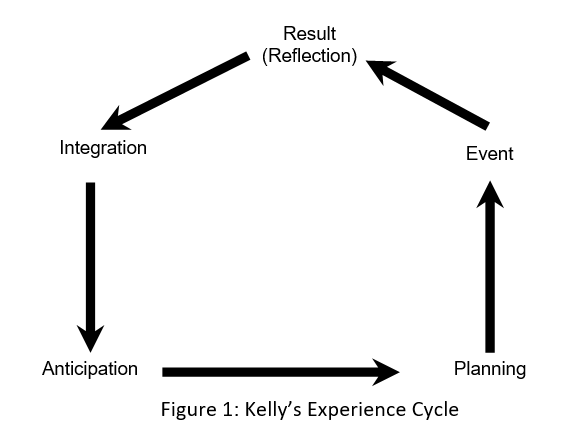

I’d like to suggest that, according to Kelly’s model, we interact with our world by approaching every situation based on our past experience of similar situations and acting “as if” this situation is the same. Once we’re through the experience we then reflect on how similar or not it was and amend our situation “map”. Figure 1 shows this cycle.

You could argue that we filter external information through a series of tried and trusted lenses which then influence our perception of the situation and how we engage with our world.

There is a constant interplay between our internal thoughts, self image and drives and how we then map these onto our external experiences (and vice versa). One of the basic tenets is that people are always in motion, mentally positioning themselves in relation to both themselves and to other people. One of the functions of this constant exchange is to make sense of our world, help us make the best choice of action and reduce uncertainty.

The process in full moves us through Anticipating an event, then we Plan (i.e. decide) what to do – something or nothing. Then we implement our plan doing what we decided to do (have an Experience), following from that we process the outcome of the interaction by Evaluating/reflecting on the consequences of that experience and assessing whether the event confirmed our prediction or not (and how). Finally, we Integrate our latest evaluation into our map of the world resulting in either a Construct revision or a tightening of our viewpoint. Then the next time we approach a similar situation, we start the cycle again and Anticipate what the outcome will be next and Plan what to do.

Psychological theory, generally, purports that we observe other people’s behaviours and actions and place our own interpretations on them, attributing meaning based on our own past (childhood) experiences. PCP is a more liberating theory, allowing the individual to develop and grow throughout their life constantly observing, assimilating, developing actions/reactions, experimenting and testing beliefs. Kelly (1955/1991) used the phrase “man the scientist” (sic) to explain how we interact with our world. Due to the constantly changing nature of our nature we are not “the victim of our biography” and have the choice (although sometimes it may not appear as such) to adopt a new way of interacting.

How we interact with others is the result of our past experiences and an assessment of the current situation which is then mapped onto possible alternative courses of action, we then chose that course of action which we think will best suit our needs. Kelly (1955/91) proposed that we are all scientists – by this he meant that we are constantly experimenting with our world, generating hypothesis about what will happen, acting, and testing the resulting outcome against our prediction. It can be seen from this that our behaviours are not static. We do not become “the adult” during childhood, nor are we forever condemned to sail the seven seas like the Flying Dutchman making the same mistakes.

PCP is a very free and empowering psychology. We are not seen as victims of circumstance, we have the power to change and grow. We are only limited in our vision of ourselves and our future by our own internal “blinkers” – these limit the possible futures we can see for ourselves and hence restrict our ability to develop.

One of the fundamental tenets of PCP is that of “Constructive Alternativism”. In simple terms this means that there are as many different interpretations of any situation and possible future outcomes as we can think of – how many different uses can you think of for a paper clip?

Our collection of experience’s and actions form the basis of our mental map (or logic bubble) of the world. In PCP terms the working tools of our mental map are known as “Constructs”. A construct is simply a way of differentiating between objects. Each construct can be equated to a line connecting two points. These two points, or poles, each have a (different) label identifying the opposite extremes of the construct. Based on our perceptions of other people’s behaviour we can then place them somewhere on the scale between the two poles and hence build our mental map of the world. We also place ourselves along these same dimensions and use them as a guide to choosing not only our behaviours but also our friends etc. As a result of our experimenting we are constantly assessing our constructs for their level of “fit” in our world. This results in either a validation of the construct or an invalidation of (and hence potential change to) our constructs. Problems occur when we consistently try to use invalidated constructs in our interactions.

For example we might define people by the way they act in company and decide that some people are “extravert” and others “introvert”, other constructs may be physical, e.g. tall or small, fat or thin. Objects can fall into more than one category so we can have small, thin extroverted people. Within Klienian psychology one example of a construct would be “Good Breast”/”Bad Breast”. One point here, the opposite of “introvert” may not be extravert for some people; it could be loud or aggressive. Hence just because we associate one with another doesn’t mean everybody does. This is why we need some understanding of other people’s construct system to be able to effectively communicate with them.

To be able to interact with each other we need to have some understanding of how the other person perceives their world. What do they mean when they call someone “extroverted”?, are they the life and soul of the party? or are they loud and over bearing? How we, and they, treat the extrovert depends on whether it is viewed it as a positive or negative character trait.

Kelly defined his theory in a formal structured way by devising what he called his “fundamental postulate” – I think this is really just a posh term for the statement which underpins the whole of PCP.

A further eleven corollaries (or clarifying statements) were also developed which extended the theory and added more elaboration to how the theory impacts and is used. These eleven have over time been expanded and added to as the range of the theory has been developed (e.g. see Dallos 1991, Procter 1981, Balnaves and Caputi 1993). In fairness it must be said that these additions have not been universally acclaimed and many people only recognise the original eleven.

You may have got the impression that PCP is very individual focused – which it is – and that it has nothing to offer in terms of group development (luckily it does – very much so). The principles of PCP can be applied to individuals, groups and culture with equal ease. Various books and papers have been published exploring the nomothetic aspects of PCP (e.g. Balnaves and Caputi 1993, Kalekin-Fishman and Walker 1996).

The Fundamental Postulate and the Eleven Corollaries

The Fundamental Postulate states that “A person’s processes are psychologically channelized by the ways in which they anticipate events”. My interpretation of this is that our expectations dictate our choice of action.

The Construction corollary – “A person anticipates events by construing their replication”. Again, I interpret this as meaning that we approach the future by looking at similar past experiences and basing our actions on those previous events.

The Experience corollary – “A person’s construct system varies as they successively construe the replication of events”. I take this to imply that our construct system is in a state of constant change based on our experiences.

The Individuality corollary – “People differ from each other in their construction of events”. We all see things differently.

The Choice corollary – “People choose for themselves that alternative in a dichotomised construct through which they anticipate the greater possibility for the elaboration of their system”. Therefore, in my opinion, we choose that alternative which gives us the best chance of extending (and confirming) our construct system.

The Sociality corollary – “To the extent that one person construes the construction process of another, they may play a role in a social process involving the other person”. If we understand where someone is coming from we can interact with them in a productive meaningful manner.

The Commonality corollary – “To the extent that one person employs a construction of experience which is similar to that employed by another, their processes are psychologically similar to of the other person”. i.e. Great minds think alike.

The Organisational corollary – “Each person characteristically evolves, for their convenience in anticipating events, a construction system embracing ordinal relationships between constructs”. This I take to mean that we create a hierarchical construct system.

The Dichotomy corollary – “A person’s construction system is composed of a finite number of dichotomous constructs”.

The Range corollary – “A construct is convenient for the anticipation of a finite range of events only”. Some constructs are applicable to certain things and not others e.g. a car may be “fast, sporty and sexy” but an apple may not be.

The Modulation corollary – “The variation in a person’s construction system is limited by the permeability of the constructs within whose range of convenience the variants lie”. By this I understand that our construct system is only as flexible as we allow it to be. If our constructs are “open to suggestion” then so will we.

The Fragmentation corollary – “A person may successively employ a variety of construction systems which are inferentially incompatible with each other”. In other words we can hold contradictory constructs at the same time.

As PCT is a dynamic theory, additional corollaries have been suggested over the years. For example, Harry Procter (1981) and Balnaves & Caputi (1993), proposed some new ways of looking at how families operate within their family environment and how organisations function within their own cultural environment respectively.

Harry proposed the following corollaries :-

The group corollary – “to the extent that a person can construe the relationship between group members, they may be able to take part in a group process with them”.

He extended this to the family (or in our case the team corollary) and said that :-

“for a group of people to remain together over an extended period of time, each must make a choice, within the limitations of their own system to maintain a common construction of the relationship in the group”.

Notice what he is saying here is not that groups are in agreement with each other just that they can see where the other members are coming from and decide to go along with, or disagree with, it within specific rules.

Balnaves & Caputi suggest that while we all have individual constructs that we use to mediate and moderate how we understand and act in the world, we also have shared, negotiated constructs that help us make sense of our organisational surroundings. These “corporate constructs” are, in effect, a map of the culture of the organisation and are the unwritten rules that help us make sense of our experience from a group perspective.

Constructs in use

Constructs form the building blocks of our “personality” and as such come in various shapes and sizes. From the Organisation corollary it follows that some constructs are more important than others. The most important constructs are those which are “core” to our sense of being. These are very resistant to change and include things like moral code, religious beliefs etc. and cause significant psychological impact if they are threatened in any way. The other constructs are called “peripheral” constructs and a change to them does not have the same impact. It also follows that some constructs will actually subsume other constructs as we move up the hierarchy.

Categories of constructs come in three types :-

- There are “pre-emptive” constructs, these are constructs which are applied in an all or nothing way. If this is a ball then it is nothing else but a ball – very black and white type of thinking.

- The second type is “constellatory” constructs. These constructs are the stereotyping constructs – if this is a ball then it must be round, made of leather and used in football matches. Constructs in this category bring a lot of ancillary baggage with them (be it right or wrong).

- The last type of construct category is “propositional”. This one carries no implications or additional labels and is the most open form of construct. Kelly uses the term “Credulous approach” to describe how we should use this category – in that we should be open minded and recognise that the individual has made the best decision they can with the information they have at that time.

It should be noted that constructs do not have to have “words” attached to them. We can, and do, have constructs which were either formed before we could speak or which has a non verbal symbol identifying it. Something like the “gut feeling” or “it feels right” would be a non verbal construct. Kelly originally called these “preverbal” constructs, but in line with others (notably Tom Ravenette 1977) I prefer the term non verbal.

Constructs, themselves, can be either Loose or Tight. A loose construct is one which may or may not lead to the same behaviour every time. Obviously this can make life difficult for others as they will be unable to predict the construer’s actions consistently. A tight construct on the other hand always leads to the same behaviour. These people are those with regular habits and firmly held views. Our creativity is helped by moving from loose to tight constructs. We start off with loose constructs, trying things out for size, seeing what works and what doesn’t, as we move towards the new we tighten up our construing, narrowing down our experimentation and so we begin making clearer associations and developing more clearly the “new”. One way of loosening our constructs is via play and imagination. By using play as an experiment we can (safely) try out new things.

The CPC cycle directs our method of choosing. The CPC cycle consists of Circumspection, Pre-emption and Control. This is basically a form of “Review, Plan, Do”. Initially we review the alternatives open to us (circumspection), narrow down the choice to one and devise a plan of action (pre-empt), finally you exercise control and do something. The cycle continues as every action leads to both a review of the success of that action as well as opening new choices.

Emotion

One of the criticisms levelled at Personal Construct Psychology (unfairly in my view) is that it does not deal with emotions. Others (e.g. Fransella 1995, McCoy 1977) have in my opinion, effectively addressed this myth; they show how constructs can, and do, work at an emotional level. The Process of Transition (Fisher 2000) is my way of linking in our emotions to help us in managing change and using the different emotional experiences as the guide to the motive behind our actions.

Kelly uses different terms to deal with emotions. He sees emotions as transitional stages and a key part of our normal life. For example threat is defined as ‘the awareness of an imminent comprehensive change in one’s core structure’, whilst fear is an incidental change in one’s core constructs. This means that the greater our belief is that the change will have a big impact on who we are and what we do the greater our resistance to that change will be and the more upset we will be. The more emotional investment we have in something the more we have to lose!

One feels guilt when one has done something which is contrary to one’s core constructs. Someone who sees themselves as ‘an honest upright citizen’ would feel guilt if caught in some dishonest act (even unwittingly). Happiness and joy are seen as support to peripheral and core constructs. Think about how happy you feel when you do something right or are complimented on something.

Tools and Techniques

PCP has a wide variety of tools and techniques at its disposal. Probably the most widely used is the “Repertory Grid” (sometimes shortened to Rep Grid”. This is a method of eliciting constructs by asking participants to compare three elements (objects, things, etc.,) and state how two are similar and different from the third. Answers are recorded in a matrix, which can then be analysed to produce a construct map. This has been used for research into a wide range of issues from business problems to psychotherapeutic interventions (some examples of the latter can be found in various chapters within this book). The Rep Grid (as it is known) has a wide following and can be used without any other PCP theory (and has been!). There are many variations of Rep Grids including those looking at resistance to change as well as implications grids and problem solving (for a more comprehensive review of grids I would suggest Beail 1985, Fransella and Bannister 1997, Stewart & Stewart 1981).

The Rep Grid can be compared to a “hard measure”, eliciting, as it does, quantifiable data. There are, however a lot of softer, more “touchy feely” construct elicitation techniques available. One of the more popular is the “Self Characterisation”. In this the client has to write a character sketch of themselves in the third person and from a sympathetic viewpoint. This can then be assessed for recurring themes and constructs, these can be discussed with the individual concerned.

A “Self-Characterisation” is a very simple technique of getting individuals’ to write something about themselves from a third party perspective. The piece must be written as if the writer knows the person very well and likes them! The usual request is to write as if the writer is describing a character in a play who is intimately known by the writer, and who the writer likes. It usually starts, in my case, with “John is ….” to avoid trying to influence the direction the description takes.

You then read the subsequent piece and look for common themes, trends and look to identify any possible constructs that will then help you understand where they’re coming from and how best to support them moving forwards.

Once constructs have been elicited their hierarchy and interlinking can be found by “Laddering” and “Pyramiding”. The former takes one upwards towards the highest core constructs whilst the latter provides a detailed map of a person’s lower level construct map in any particular area. By asking questions like “which is more important a or b?” and then asking “why” questions one can ladder quite quickly and easily.

Pyramiding, on the other hand, requires questions like “what kind of person does y?”, “How does that/they differ from x?”, this process allows the client to narrow down their definitions and arrive at the lower level constructs. This exercise does require a reasonable sized piece of paper to record all the answers and provide a sensible construct map.

One powerful tool for understanding why people are not willing to change is the “ABC technique” (Tschudi 1977). Here A is the desired change with constructs B1 and B2 elicited. B1 being the disadvantages about the present state and B2 the advantages about moving to the new state. However it is possible (if not probable) that the current situation has some advantages which may outweigh the disadvantages. Therefore C1 are constructs which show the negative side of moving whilst C2 are the positive aspects of staying the same. But, by looking at the pay-offs for not changing we can identify the barriers and put measures in place to overcome them (if necessary).

Kelly also proposed a form of dramatherapy for use with clients. In his version, which he called “Fixed Role Therapy”, in conjunction with the client he drew up a new persona (including a new name and history) and encouraged the client to act as if they were this new person. This allowed the client to “try out” new ways of looking at the world in a safe environment (if it didn’t work they just became themselves again). Hypnotherapy has also been used to loosen (and tighten) constructs.

Conclusion

I hope that this brief introduction to PCP has shown some of the breadth and depth of PCP. Far from being a static, restrictive psychology that only perceives people as having finished growing at the end of childhood or merely reacting to external stimulation, it is an extremely liberating and eclectic psychology. Ownership of one’s own future is placed in the hands of the individual concerned.

References

Balnaves M. & Caputi P., 1993, Coporate Constructs; To what Extent are Personal Constructs Personal? , International Journal of Personal Construct Psychiology, 6, 2 p119 – 138

Beail N, (ed), 1985, Repertory Grid technique and Personal Constructs, Croom Helm,

Dallos R. (1991), Family Belief Systems, Therapy and Change, Open University Press, Milton Keynes

Fisher J. M. (2000), Creating the Future?, in Scheer J W (ed), The Person in Society: Challenges to a Constructivist Theory, Geissen, Psychosozial-Verlag, ISBN 3898060152

Fransella F. (1995), George Kelly, Sage, London

Fransella F. and Bannister D. (1977), A Manual for Repertory Grid Technique, Academic Press, London

Kalekin-Fishman D, & Walker B. (eds) 1996, The Construction of Group Realities: Culture, Society, and Personal Construct Theory, Krieger, Malabar

Kelly G. A. (1955/1991), The Psychology of Personal Constructs, Routledge, London

McCoy M. M. (1977), A Reconstruction of Emotion, in Bannister D (ed), Issues and Approaches in Personal Construct Theory, Academic Press, London

Procter H. (1981), Family Construct Psychology, in Walrond-Skinner S (ed), Family Therapy and Approaches, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

Ravenette T. (1977), Selected papers: Personal construct Psychology and the practice of an Educational psychologist, EPCA Publications, Farnborough

Stewart V. & Stewart A. (1981), Business Applications of Repertory Grid Technique, McGraw Hill,

Tschudi F. (1977), Loaded and Honest Questions, in Bannister D (ed), New Perspectives in Personal Construct Theory, Academic Press, London